Wine, Cyder and Perry

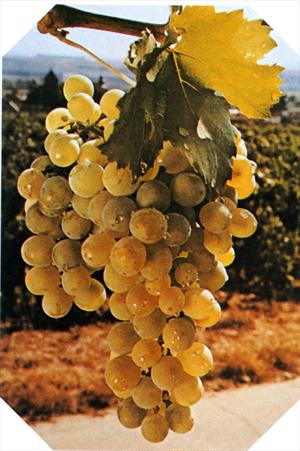

Müller Thurgau

Wines are regarded by Her Majesties Customs and Excise as drinks which contain at least 8.5% ethyl alcohol, by volume. The majority of cyders and perries have less than 8% and are not wines within this definition. Apple and pear wines which are fermented from mainly dessert fruit and water and have had sugar added to achieve 10% or higher alcohol content are wines by Custom and Excise definition. Home-made wines are fermented from 'mashes' of almost any fruit or flower or vegetable with water. Their alcohol content may reach 18% - the maximum tolerated by the most macho of yeast's - and depend almost entirely upon the amount of sugar added to the mash for their alcohol content. Beers have 3-5% alcohol and are not wines, but Barley wine at 10.5% is. Mead, melomel, pyment, hippocras, cyser and methaglin are wines fermented from honey in water and the alcohol content potential is decided by the amount of honey-sugars contained in the 'mash' or 'must'.

Home-made wines taste of the added fruit, vegetable or flower; cyder and perry taste of apple or pear; but grape wines seldom taste of grape - with the exception of muscats. An oenological definition for wine regards it as that which results when the unadulterated juice of grapes, with no added sugar or water is fermented by a yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, or its variety, ellipsoideus or subvarieties, although this definition may be relaxed in operation. The Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) through its Apple and Pear Produce Liaison Committee (APPLE ) defines Category 'A' cyder and perry as ’having been fermented from the undiluted juice of cyder apples or perry pears from a single source - English, French, German, Swiss, Somerset etc. And so they may be considered as wines within the ‘pure juice’ definition.

There are many wines which have been made with scant regard for the most lax of definitions and in my opinion, the most unconscionable are from some factory wineries which carry the brand names of some globalised concerns. Maximising profit drives these wines in a number of ways: the grapes are left on the vine until overripe and may be exported also to less 'sunny' wine makers; the sugar content is brought down to the required level by adding water; high sugar results in low acid and so tartaric acid is added to 'balance' the wine; the diluted colour of reds is enhanced with colorant; bags of oak chips are sunk into the wine to 'barrel mature' it, and so the wine may be marketed earlier than 'real' wine and possess little more than nodding acquaintance with its original vines. Some ciders and perries, too, are shameful commercial parodies and result from bulking musts with cheap Chinese Golden Delicious pulp, although APPLE Category ‘B’ must not be entirely from concentrate.

This promotion of reward over regard for quality is nothing new, for it has ever been that some do themselves proud whilst exploiting those whom they may. Cider was a safe alternative to water and it was the practice to part pay farm labourers with cyder - a safe re-hydrator for manual workers. The well off delighted in fine cyders and perries. One noble Lord would have his cyder made only from apple skins, where lies much of the richness and bouquet. The quality of that which came to the labourer went from bad to worse, until it was said ‘If had been better, we wouldn’t have got it: worse and we couldn’t have stomached it.’

A more up-to-date exemplar of quality range lies in some fairly recent scientific research into Vitamin C, which found that ‘cider’ contained only 3mg/litre and was of no practical value as an antiscorbutic. It followed that the old Naval report that ‘cyder, administered to a sailor whose teeth were loose from scurvy and a 'dying, made him better in two days and fit for work in a week' was insupportable. However when the experiment was repeated, using a less 'commercial’ sample the content was found to be 47mg/litre, which is far more than the minimum daily requirement.

Not only Terroir but Tradition

It is my good fortune to have enjoyed the friendship of a Mosel wine growing family for some 25 years. Much of my wine making approach has come from them, but the most important fact which has come my way is the knowledge that whilst we may make wine in Britain, they live it! If you wish to be a winemaster, it helps if an ancestor married into your wine domain in 1604! Each vintage passes on an accumulation of tradition, winecraft, art, working with Nature and in a continuing wine environment. A year is 12 months of vine and wine. and the wine village is interwoven with its vineyards. My friend's wine village supports two butchers, two bakers, a market gardener, a hunter and a smokehouse! It grows its stakes and barrels. There is a Sektmaker (fizz), a brandy distiller and a liqueur maker and the pulse of the village depends upon the state of the grapes. It takes no great leap of imagination to see a similar holism and philosophy in our land dependent forefathers.

If Britain has a wine or cyder tradition then it has been fragmented a number of times, by cold periods, bad kingship, neglect and snobbery. We hear great things of our wines' increasing excellence, but the new wave is yet young. Perhaps our 'wine tradition' will be dated from Sir Guy Salisbury-Jones 1952 Hambledon vineyard and if so, then a 2052 judgement will have credence. We can make, most certainly, good table wines and fizz. Let that be sufficient nationalist massage for now!

It is said that global warming will improve our wines. I suggest that whilst it will increase the number of varieties from which we can choose, it is light intensity which drives the taste forming reactions within the berry and our light intensity is most likely to deteriorate. Nevertheless, there are many English and Welsh wines far, far better than the factory-wines with which we are assailed by our supermarkets. Try them!

Buying Wine, Cyder and Perry

I make no pretence to being a wine buff, but I believe that I should do the choosing -not the vendor! I do buy in the supermarket, but hopefully with eyes wide open. I reason that since the unit supermarket shelf length must show unit profit over unit time, it follows that ‘This week only Mongolian Chardonnay - Was £7.99 now ONLY £3.99' ... shows a profit and suggests to me that any sale at £799 was extortionate, probably brief and by ‘marketing arrangement’ with the brand owner. Not fair trading by my standard and so I leave it there!

The top 40 brands are owned by about half a dozen globalised companies. They control the bulk of the wine market. The wine sellers' magazine The Drinks Business makes great play on the vendor's need to encourage 'Brand Loyalty' in the marketplace'. Cane Frog's Leap, Chile Dawn, Randy Gold may be worth the 'half’ price, but as a well known wine-columnist put it - 'Supermarkets err, most usually, on the safe side of bland.’

I look for a winegrower's name or a co-operative or a named grape which is not in the ‘popular list' and try it. I would not go to a supermarket if I wished for a 'fine' wine, having been standing vertically in bright light and in heat over time? Better, I believe, to buy from one of the choosier Mail order firms, but never the vendor's mix or a ‘Fine’ wine merchant.

Home-grown wine

Producing one’s own home-grown wine can begin only at least two and preferably three years after planting. The varieties from which we may choose are winter hardy and just as a dessert apple makes a disappointing cooker, dessert grapes make disappointingly flabby wine. Some wine varieties make good eating as do some general purpose apples. It is most important that you have a style in mind before planting, since the vine will, almost certainly, outlive you! With the reservation that there is, as yet, no hybrid vine which is superior to Vitis vinifera varieties. Only some of the hybrid vines show considerable resistance to mildews, but take care for some produce ghastly 'foxy' wines and seedless grapes are too short of tannin to be of wine use. It is my opinion that vines do best on their own roots and that whilst we are free from grape-louse (Phylloxera vastatrix) they should be so; grafting on phylloxera resistant rootstock doubles the price of the plant. I am neither fundamentalist organic nor inorganic and so I accept that if I wish is to grow a particular variety and it is European in origin, then spraying is almost unavoidable and it must be remembered that having experienced mildew once, then it is an inevitability in the future.

Grape Varieties

Müller Thurgau and Seyvre-Villard 5276 (Seyval) were the most grown 'whites' until the late eighties and having been planted they are bound to be favoured by many, but there are better. Müller Thurgau and Seyval blends can be good but Müller Thurgau has too many faults for me and Seyval needs very careful fermenting for it can be insipid and toweringly acid. Seyval, however, has good mildew resistance. I like Schönberger and also Zala-Gyöngye, which I have been trialling for Brian Edwards for about 5 years. Zala-Gyöngye is a Hungarian mildew resistant hybrid which is at the heart of many eastern and southern European wines of poor quality, but it has produced pleasant wines for me. Our long ‘season of soft mists and mellow fruitfulness’ suits it well, as it does a number of other 'Europeans', especially German whites.

Seibel 13053 has been the workhorse red for a long time and it is dependable and mildew resistant, but it needs long maturation to attenuate the tannins. Favourite reds in the west are Marshal Joffre and Triomphe d’Alsace, both are early and blend well. More recent introductions are Dornfelder, which was thought would become the red here, but it seems that we are just outside its provenance. I grow it under cold glass, and it behaves well, and Rondo which

can make very good wine and has some resistance to mildew but can be a martyr to botrytis. Gagarin Blue makes good wine. It has no disease resistance but has very open bunches and is good to eat, as is Dornfelder.

Alan Rowe

Photograph taken from Successful Grape Growing for Eating and Wine -Making by Alan Rowe, 3rd edition 2006, published by Groundnut Publishing

Published: 18 Nov 07

Author: Alan Rowe

To comment on this article please visit our blog.